In the case of Wuli Village, the team’s most important work was not transformation, but understanding. They spent extensive time researching the region’s geography, ethnic communities, religious practices, crafts, and building traditions—seeking to develop a way of seeing from within the place itself, rather than looking down upon the countryside through an urban lens.Lai emphasized that design begins with cultural humility. It is not about replacing an existing way of life with a supposedly “better” one, but about finding an appropriate scale of intervention through respect—allowing renewal to become a form of continuity, rather than an act of erasure.

In Wuli Village, service cannot be “instant,” circulation is not designed for “efficiency,” and many spaces still retain the slow order of traditional architecture. Lai Guoping does not shy away from the inconveniences that come with such choices. In his view, dwelling is never the outcome of efficiency. The real question is: why do people travel to places like this in the first place? If every destination is eventually reshaped into yet another familiar version of the city, then the meaning of travel is gradually exhausted.When asked whether upholding this practice of slowness has come at a great cost, his answer was strikingly direct: it is not a cost, but a form of compensation — a counterbalance to an age of excessive efficiency and mechanical progress. The value of Wuli Village lies precisely in the fact that it still asks people to give their time, to truly arrive, and to truly stay.

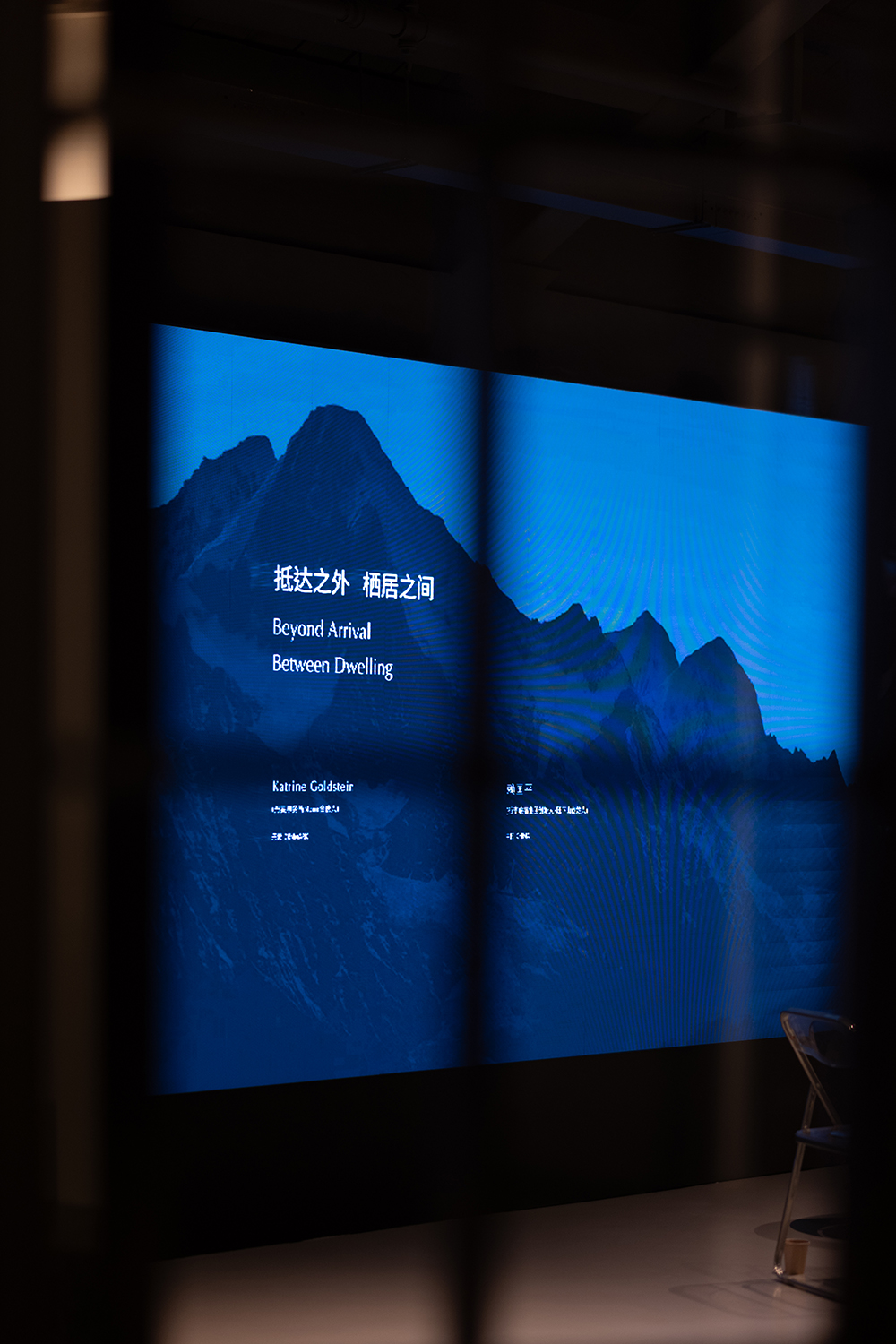

In the closing of his talk, Lai Guoping also chose to end with a short film. The camera moved through the long rainy season and drifting mist of the Nujiang Gorge, finally arriving at the village’s timber houses and the faint glow of the fire pit. In that moment, “the distant” was no longer merely an idea, but something unmistakably real — a geographical distance, and a way of life that can only be reached through time.