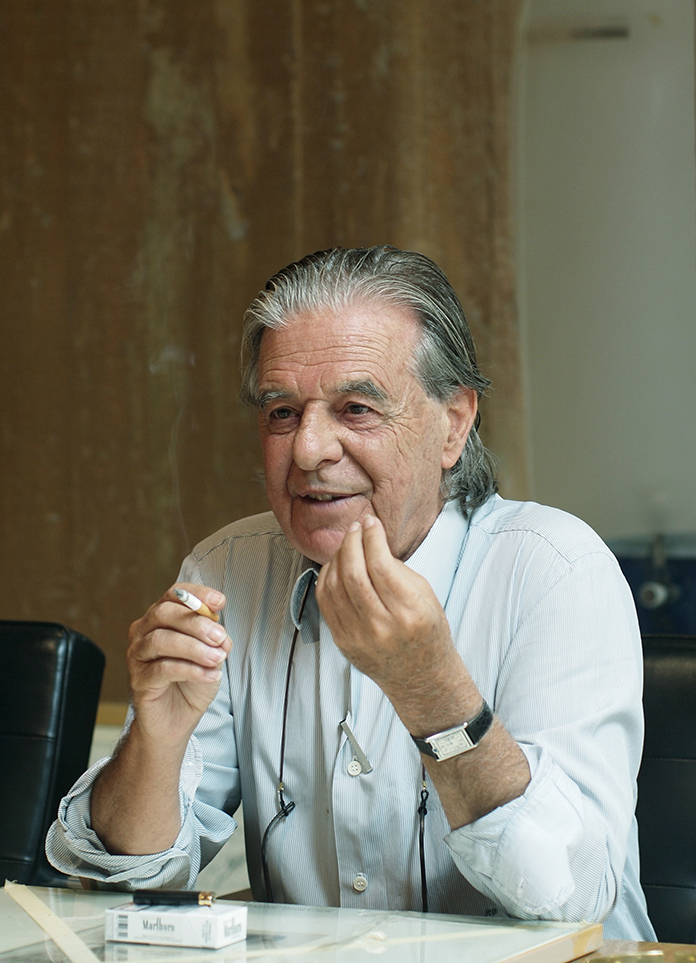

In this ever-accelerating world, we have grown accustomed to measuring value with numbers and defining space by function, gradually neglecting the intangible yet deeply rooted elements: atmosphere, rhythm, and the emotional relationship between people and space. What I’ve been seeking is a design language that speaks to the soul—not the loud novelty of the “new,” but the quiet, enduring strength of the “eternal.”Then one day, I casually opened my design archive and was struck by a realization: nearly all the works that moved me came from the same place—Belgium. From Axel Vervoordt’s Wabi-Sabi philosophy to Vincent Van Duysen’s poetic spatial order, these works are quiet yet resolute, restrained yet powerful. They do not need to be explained or emphasized—their mere existence is already the most touching form of expression.

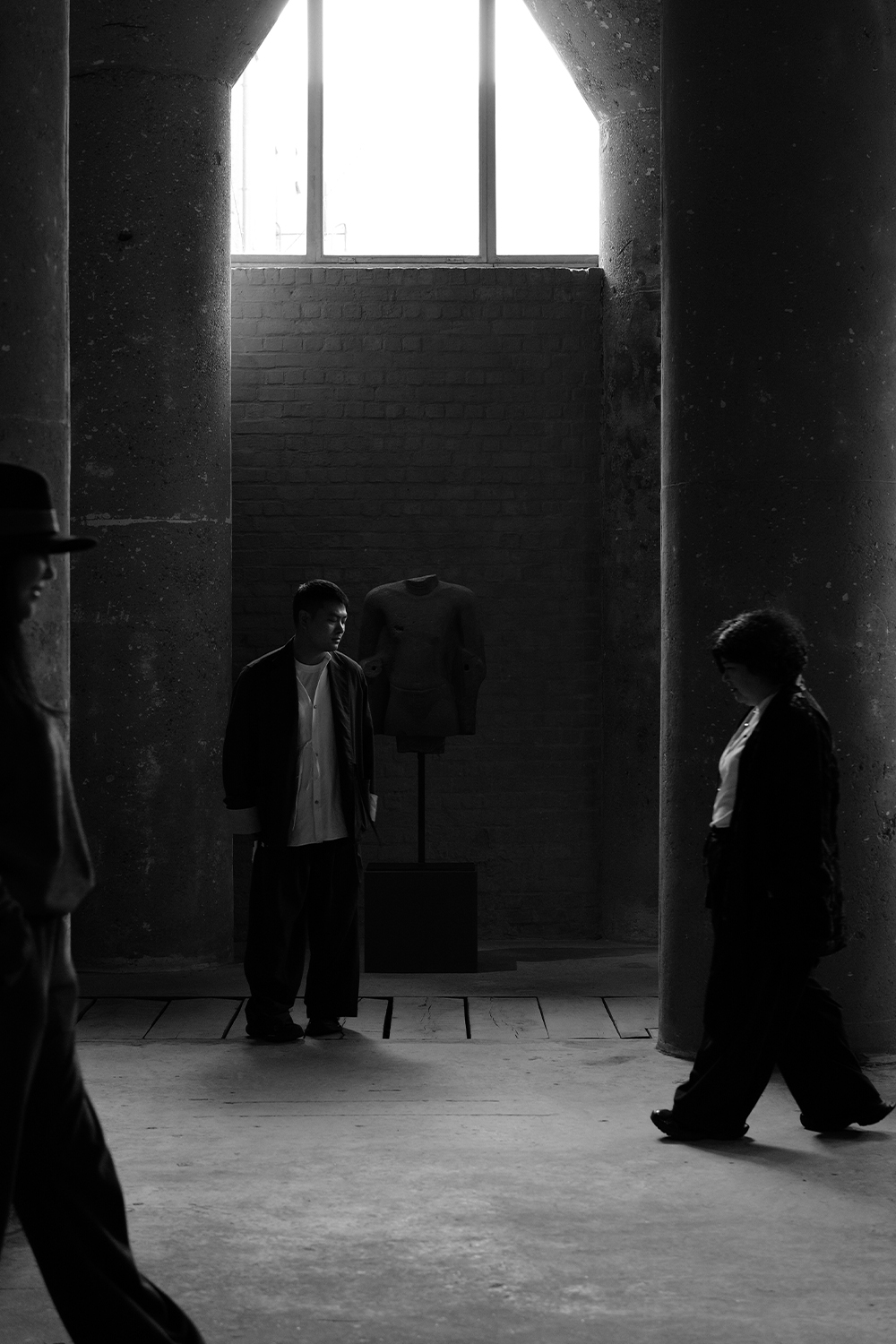

And so, I decided to embark on a journey—to personally experience how this land fuses history, nature, and the contemporary, and how seemingly effortless expression can return space to its human essence. Though I had visited Europe many times and studied design there, this was my first time setting foot in Belgium. With clear purpose and immense curiosity, we embarked on a 7-day intensive study tour. Though brief, the journey was densely structured, covering a full spectrum from cultural roots to contemporary expression.

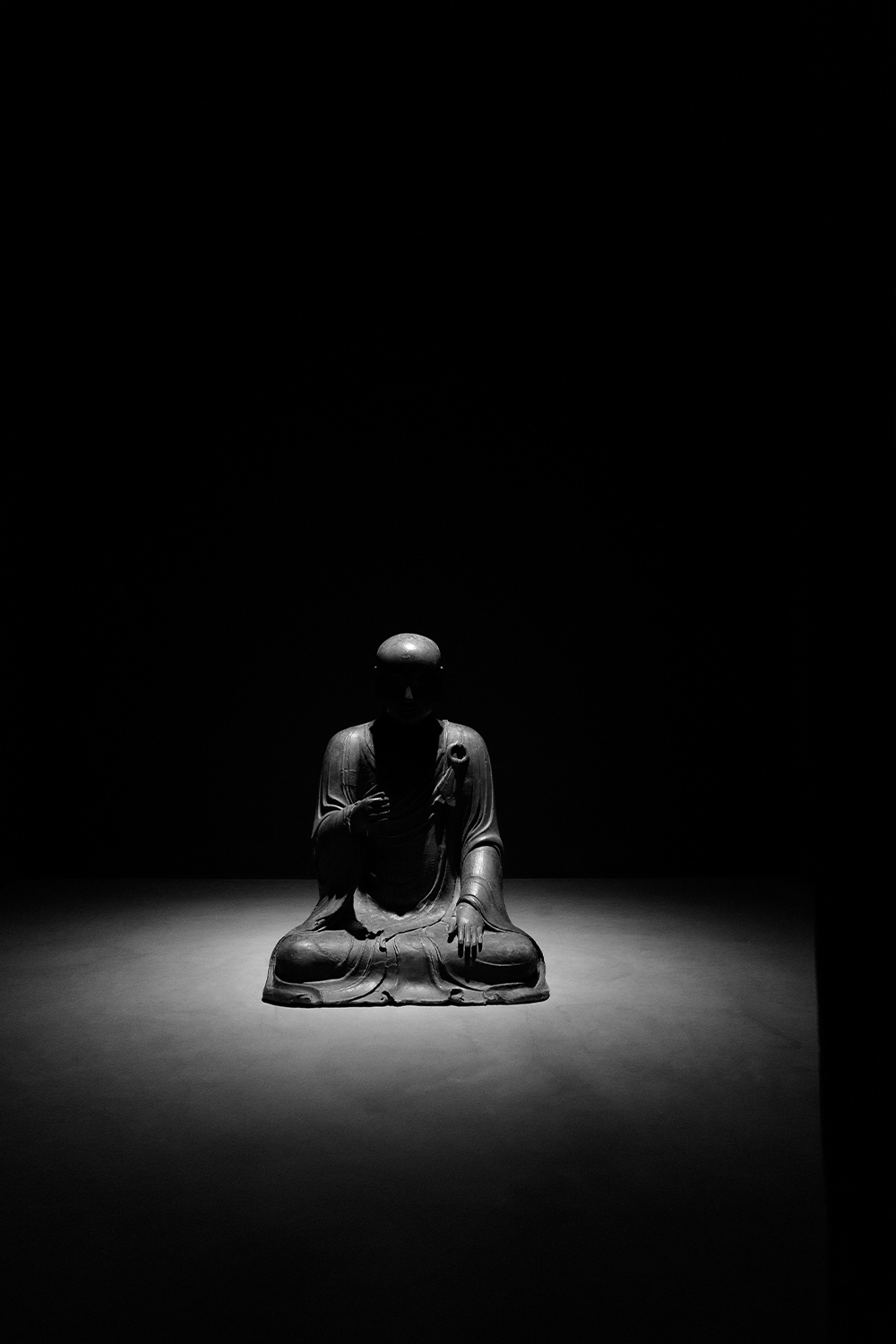

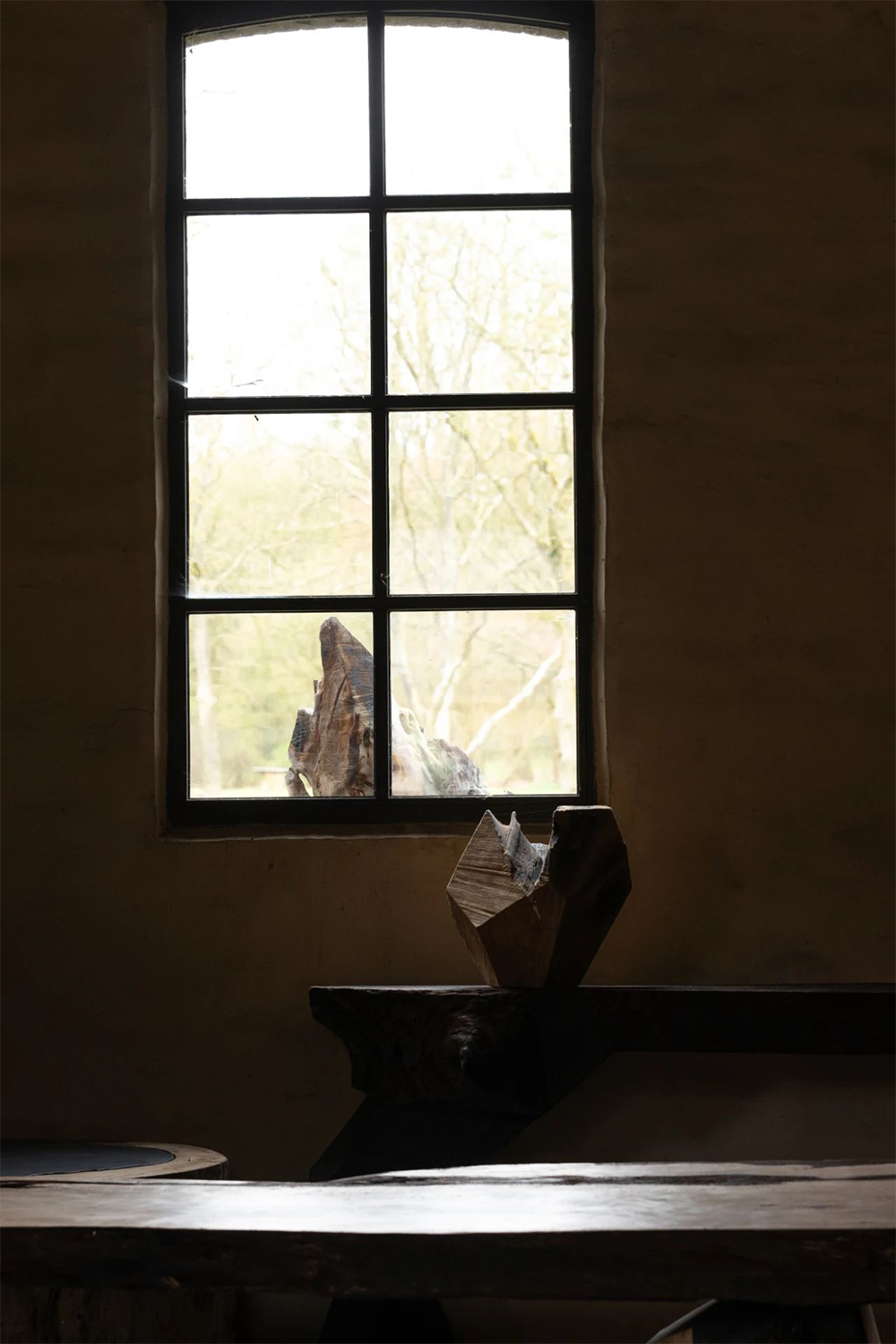

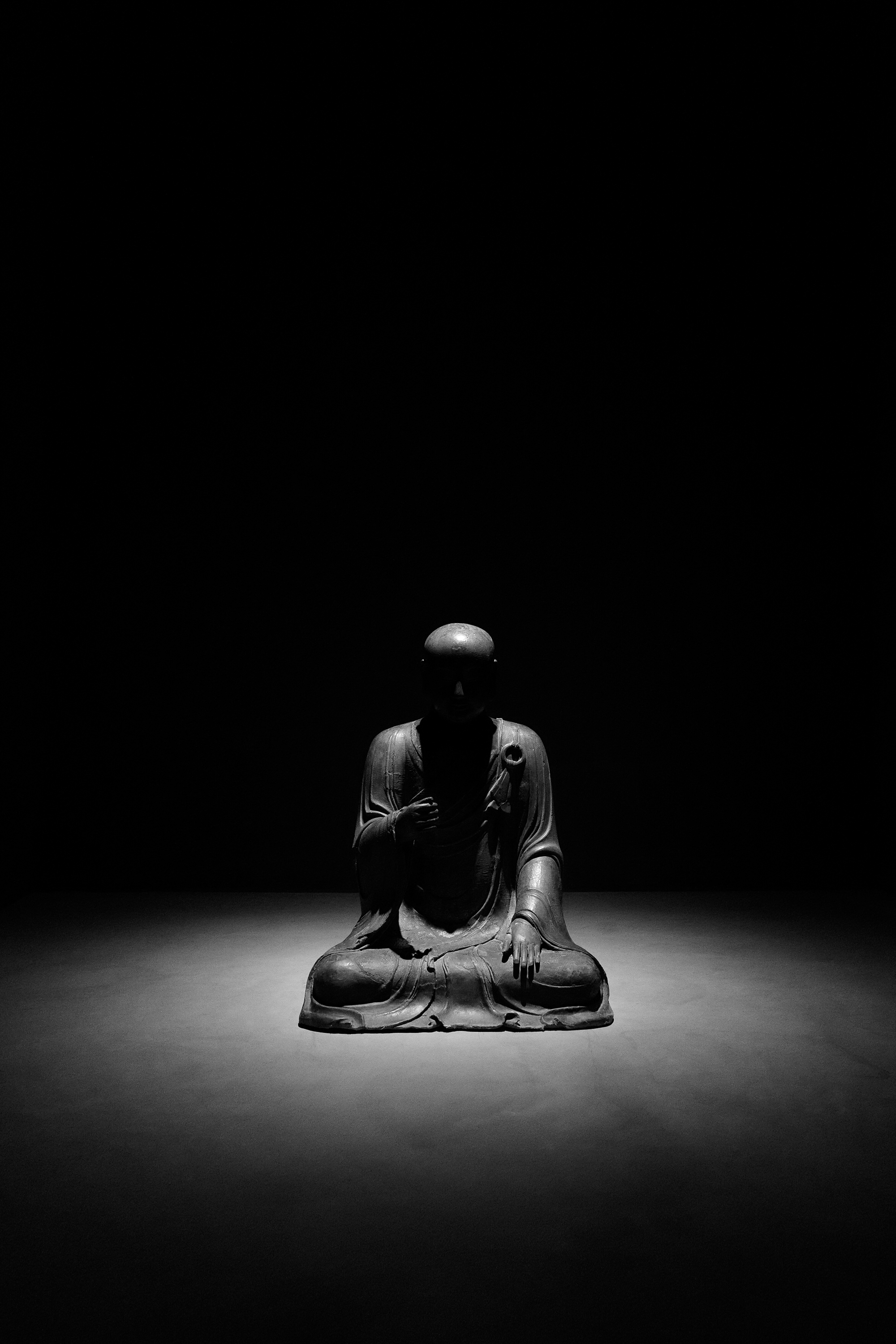

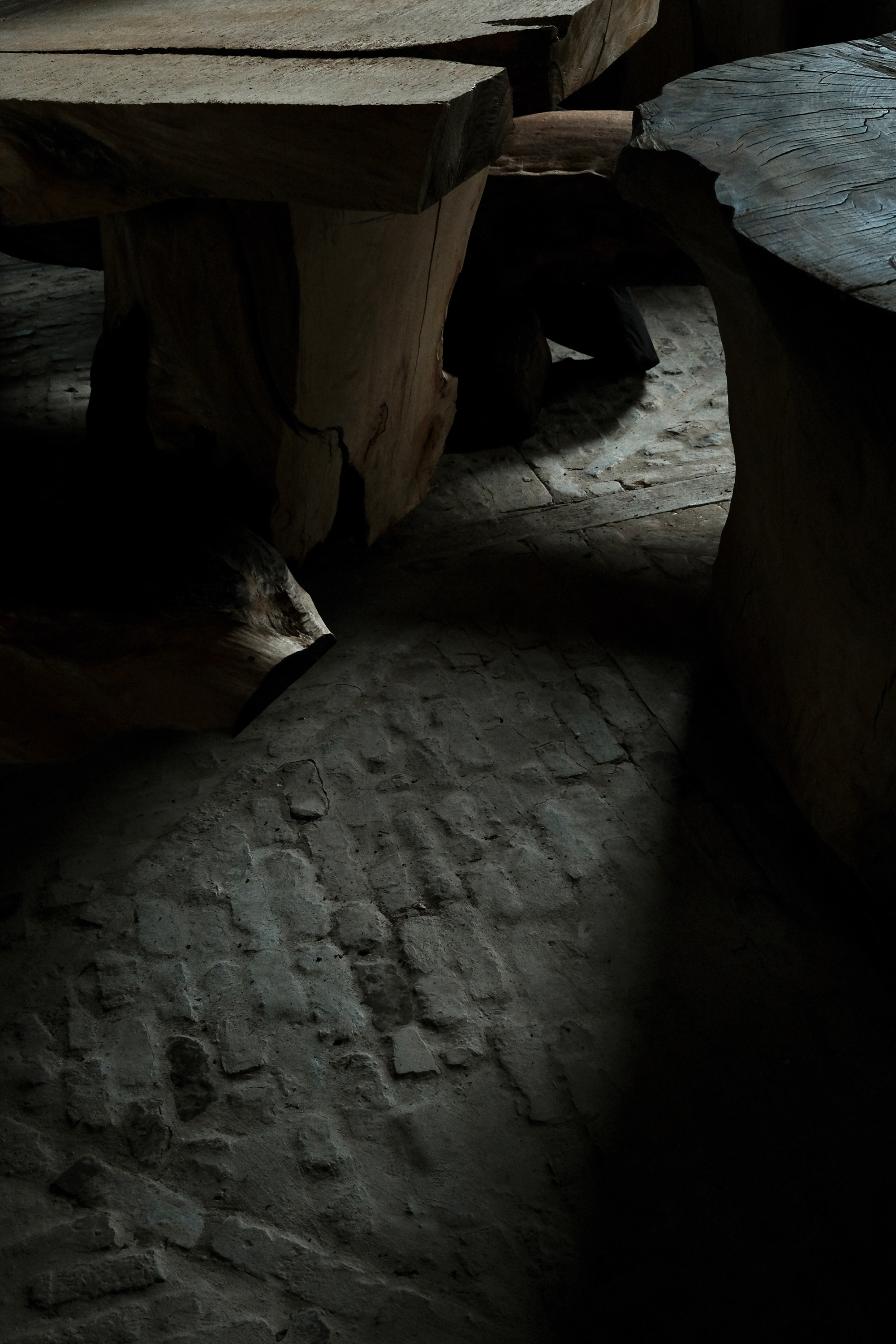

Our first stop was the material research space of Cédric Etienne. As a representative of the new generation of Belgian design spirit, he redefines the relationship between materials, people, and space through natural energy. Here, materials do not exist for display but return to their essence—they have their own scent, temperature, and breath. You see no deliberate staging, no familiar industrial odors. Instead, a highly restrained expression lets texture, light, and materiality take center stage.

Here, design does not wrap materials—it lets them speak for themselves. And when they are genuine and natural enough, they possess a spiritual texture that commands admiration. This is not just a difference in design methodology—it is a difference in life philosophy. They believe materials have souls, spaces have emotion, and design is merely a way to awaken them.