On a grey March day softened by the quiet blush of sakura, we arrived at Frederic Kielemoes' private residence, tucked discreetly behind the Flemish landscape. It is not, strictly speaking, a home. Nor is it a gallery, nor an office. “A pavilion,” Frederic explained as we crossed the threshold in hushed groups of five or six, “not a residence.” And immediately, everything clicked into place.

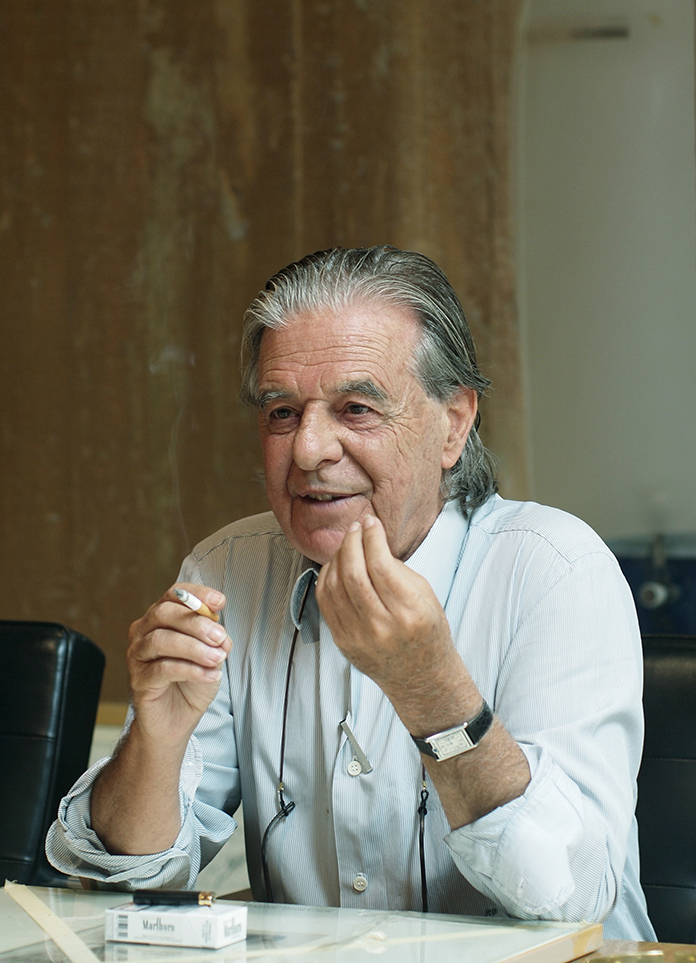

It made sense, of course — especially coming from Frederic Kielemoes himself, a Belgian interior architect revered for his minimalist design ethos. His work is quiet but deeply assured: defined by a keen sensitivity to light, proportion, and emotional tone. Kielemoes composes spaces the way some compose poetry — spare, intentional, and luminous when seen under the right light. His is a simplicity sharpened to a fine point : elegant in thought, refined in taste, and committed to transforming space into something subtly extraordinary.

This was not a house designed to perform domesticity. Rather, it suspends it, reframes it. There are almost no doors — just three, in fact, for the toilet, the dressing room, and the laundry room. Instead, long curtains soften and divide space with theatrical elegance. A gesture of openness, yes, but also of quiet concealment. This is a house that understands ambiguity as an architectural tool.